From addiction to everyday decision-making, impulsivity shapes much of our behaviour. Now, new research sheds light on how dopamine, reward size, and learned expectations combine to nudge us towards premature actions—even when we know better. By demonstrating that impulsivity increases with the value of anticipated rewards, the study offers a fresh perspective on why we sometimes undermine our own best interests.

Why do we sometimes act impulsively, even when we know it will cost us? A new study led by Professor Eran Lottem from the Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences (ELSC) at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem provides a compelling answer: impulsivity is a predictable result of how our brains process value.

Published in the journal Biological Psychiatry, the study reveals that the more valuable a reward is perceived to be, the harder it becomes to resist the temptation to act prematurely—even when patience would yield a better outcome. This paradox suggests that impulsive behaviour can be understood as a form of Pavlovian bias, where the mere anticipation of a reward automatically triggers action, even when that action is inappropriate.

To investigate this phenomenon, Professor Lottem and his colleagues—including Zhe Liu, Robert Reiner, and Professor Yonatan Loewenstein—trained mice to perform a waiting task, requiring them to delay their response to receive water rewards of varying sizes. The researchers found that the mice were significantly more likely to act prematurely when larger rewards were at stake.

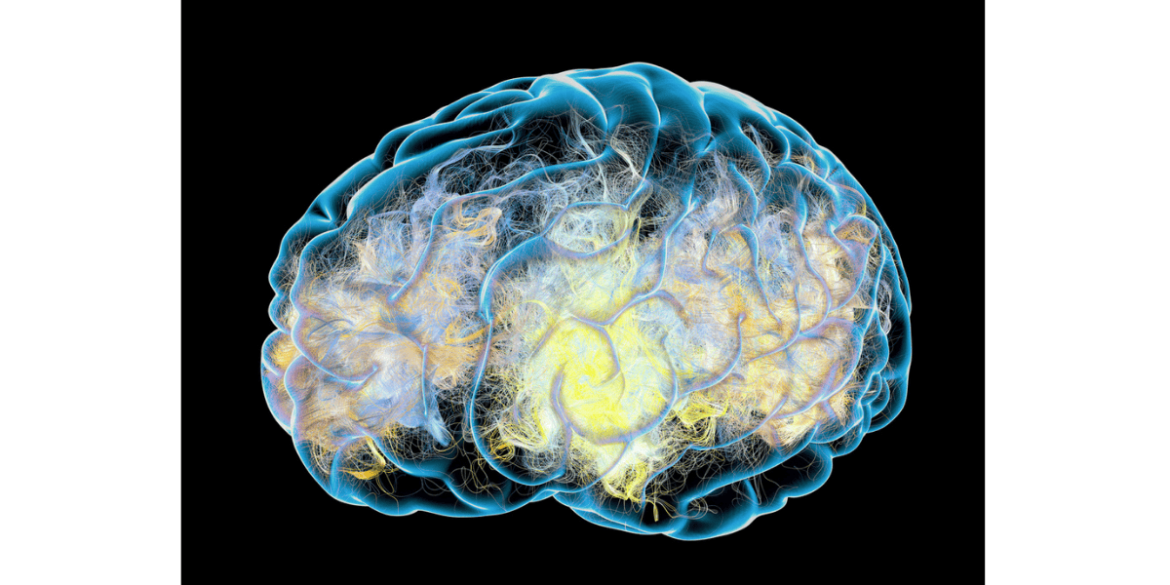

The team developed a computational model of reinforcement learning that incorporated Pavlovian bias to account for this behaviour. Using fibre photometry, they monitored dopamine release in the ventral striatum—a brain region involved in value learning and decision-making—and employed optogenetic stimulation to manipulate dopamine signals directly. Their findings confirmed that dopamine activity both predicted and influenced the animals’ impulsivity, with larger expected rewards driving a greater urge to act.

“Our results show that impulsive behaviour isn’t necessarily irrational—it’s often linked to how we’ve learned to value outcomes over time,” said Professor Lottem. “The brain’s reward system can push us to act before we think, especially when high-value rewards are involved.”

These insights may have important implications for understanding impulse-control disorders such as ADHD, gambling, and addiction. By linking impulsivity to reward valuation and dopamine dynamics, the study offers a new framework for investigating—and potentially treating—self-defeating behaviours.

The research paper, “Value Modulation of Self-Defeating Impulsivity,” is now available in Biological Psychiatry and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2024.09.017.

Researchers:

Zhe Liu, Robert Reiner, Yonatan Loewenstein, Eran Lottem

Institutions:

- Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

- Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, Department of Cognitive and Brain Sciences, and The Federmann Center for the Study of Rationality, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel